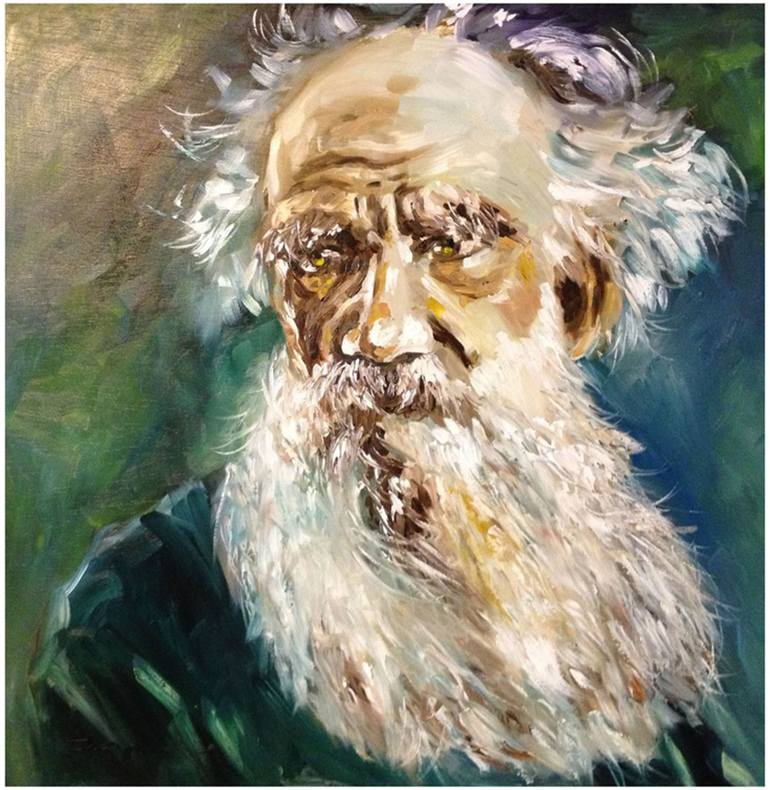

Chapter 5 War Peace and War Again

Leo Tolstoy Archive

War and Peace

Book x, Affiliate 5

1812

Written: 1869

Source: Original Text from Gutenberg.org

Transcription/Markup: Andy Carloff

Online Source: RevoltLib.com; 2021

From Smolénsk the troops continued to retreat, followed by the enemy. On the tenth of August the regiment Prince Andrew allowable was marching along the highroad past the avenue leading to Baldheaded Hills. Heat and drought had continued for more than iii weeks. Each day fleecy clouds floated across the sky and occasionally veiled the sun, just toward evening the sky cleared once again and the dominicus set in reddish-brown mist. Heavy night dews lonely refreshed the world. The unreaped corn was scorched and shed its grain. The marshes stale upward. The cattle lowed from hunger, finding no nutrient on the sun-parched meadows. Only at night and in the forests while the dew lasted was at that place whatsoever freshness. But on the road, the highroad forth which the troops marched, there was no such freshness even at dark or when the road passed through the forest; the dew was imperceptible on the sandy grit churned upwards more than half dozen inches deep. Equally soon as day dawned the march began. The artillery and luggage wagons moved noiselessly through the deep dust that rose to the very hubs of the wheels, and the infantry sank talocrural joint-deep in that soft, choking, hot dust that never cooled even at night. Some of this dust was kneaded by the feet and wheels, while the rest rose and hung like a cloud over the troops, settling in eyes, ears, hair, and nostrils, and worst of all in the lungs of the men and beasts as they moved along that road. The higher the sun rose the higher rose that cloud of grit, and through the screen of its hot fine particles one could look with naked eye at the sun, which showed similar a huge crimson brawl in the unclouded sky. At that place was no current of air, and the men choked in that motionless atmosphere. They marched with handkerchiefs tied over their noses and mouths. When they passed through a hamlet they all rushed to the wells and fought for the h2o and drank it downwards to the mud.

Prince Andrew was in control of a regiment, and the management of that regiment, the welfare of the men and the necessity of receiving and giving orders, engrossed him. The called-for of Smolénsk and its abandonment fabricated an epoch in his life. A novel feeling of anger against the foe made him forget his own sorrow. He was entirely devoted to the affairs of his regiment and was considerate and kind to his men and officers. In the regiment they chosen him "our prince," were proud of him and loved him. But he was kind and gentle but to those of his regiment, to Timókhin and the like—people quite new to him, belonging to a unlike earth and who could not know and empathise his by. As soon equally he came across a former acquaintance or anyone from the staff, he bristled up immediately and grew spiteful, ironic, and cynical. Everything that reminded him of his past was repugnant to him, and then in his relations with that former circle he confined himself to trying to do his duty and not to be unfair.

In truth everything presented itself in a dark and gloomy light to Prince Andrew, especially subsequently the abandonment of Smolénsk on the 6th of August (he considered that it could and should have been dedicated) and after his sick father had had to flee to Moscow, abandoning to pillage his dearly beloved Bald Hills which he had built and peopled. But despite this, thank you to his regiment, Prince Andrew had something to think about entirely apart from general questions. Ii days previously he had received news that his male parent, son, and sister had left for Moscow; and though there was nothing for him to do at Baldheaded Hills, Prince Andrew with a characteristic want to foment his own grief decided that he must ride in that location.

He ordered his horse to exist saddled and, leaving his regiment on the march, rode to his male parent'southward estate where he had been born and spent his childhood. Riding by the pond where at that place used ever to be dozens of women chattering as they rinsed their linen or trounce it with wooden beetles, Prince Andrew noticed that there was not a soul about and that the little washing wharf, torn from its place and half submerged, was floating on its side in the eye of the pond. He rode to the keeper's lodge. No 1 at the stone entrance gates of the drive and the door stood open. Grass had already begun to grow on the garden paths, and horses and calves were straying in the English park. Prince Andrew rode upwards to the hothouse; some of the glass panes were broken, and of the trees in tubs some were overturned and others stale upwardly. He chosen for Tarás the gardener, simply no one replied. Having gone round the corner of the hothouse to the ornamental garden, he saw that the carved garden argue was broken and branches of the plum trees had been torn off with the fruit. An old peasant whom Prince Andrew in his childhood had often seen at the gate was sitting on a greenish garden seat, plaiting a bast shoe.

He was deafened and did not hear Prince Andrew ride upwards. He was sitting on the seat the erstwhile prince used to like to sit on, and abreast him strips of bast were hanging on the broken and withered branch of a magnolia.

Prince Andrew rode up to the house. Several limes in the old garden had been cut downward and a piebald mare and her foal were wandering in front of the house among the rosebushes. The shutters were all closed, except at one window which was open. A little serf male child, seeing Prince Andrew, ran into the business firm. Alpátych, having sent his family away, was lone at Bald Hills and was sitting indoors reading the Lives of the Saints. On hearing that Prince Andrew had come, he went out with his spectacles on his olfactory organ, buttoning his glaze, and, hastily stepping upward, without a word began weeping and kissing Prince Andrew's genu.

Then, vexed at his ain weakness, he turned away and began to report on the position of affairs. Everything precious and valuable had been removed to Boguchárovo. 70 quarters of grain had as well been carted abroad. The hay and the spring corn, of which Alpátych said there had been a remarkable crop that year, had been commandeered past the troops and mown downwardly while however dark-green. The peasants were ruined; some of them too had gone to Boguchárovo, just a few remained.

Without waiting to hear him out, Prince Andrew asked:

"When did my father and sister leave?" meaning when did they leave for Moscow.

Alpátych, understanding the question to refer to their divergence for Boguchárovo, replied that they had left on the 7th and again went into details concerning the manor management, asking for instructions.

"Am I to let the troops have the oats, and to accept a receipt for them? Nosotros have still half dozen hundred quarters left," he inquired.

"What am I to say to him?" idea Prince Andrew, looking down on the old man'due south bald head shining in the sun and seeing by the expression on his face that the old man himself understood how untimely such questions were and only asked them to allay his grief.

"Yeah, allow them have it," replied Prince Andrew.

"If you noticed some disorder in the garden," said Alpátych, "it was impossible to prevent information technology. Three regiments have been here and spent the dark, dragoons mostly. I took down the name and rank of their commanding officer, to hand in a complaint nearly it."

"Well, and what are you going to practise? Will you stay here if the enemy occupies the identify?" asked Prince Andrew.

Alpátych turned his face to Prince Andrew, looked at him, and suddenly with a solemn gesture raised his arm.

"He is my refuge! His will be done!" he exclaimed.

A grouping of bareheaded peasants was budgeted beyond the meadow toward the prince.

"Well, skillful-by!" said Prince Andrew, bending over to Alpátych. "You must become away likewise, take away what you can and tell the serfs to go to the Ryazán estate or to the one nigh Moscow."

Alpátych clung to Prince Andrew's leg and burst into sobs. Gently disengaging himself, the prince spurred his horse and rode down the avenue at a gallop.

The old human was still sitting in the ornamental garden, like a fly impassive on the face of a loved one who is expressionless, borer the last on which he was making the bast shoe, and two lilliputian girls, running out from the hot firm carrying in their skirts plums they had plucked from the trees there, came upon Prince Andrew. On seeing the young chief, the elder one with frightened look clutched her younger companion by the hand and hid with her behind a birch tree, not stopping to pick up some greenish plums they had dropped.

Prince Andrew turned abroad with startled haste, unwilling to let them run across that they had been observed. He was sorry for the pretty frightened lilliputian girl, was afraid of looking at her, and yet felt an irresistible want to do so. A new sensation of comfort and relief came over him when, seeing these girls, he realized the existence of other human interests entirely aloof from his ain and just as legitimate as those that occupied him. Evidently these girls passionately desired one matter—to conduct away and eat those dark-green plums without existence caught—and Prince Andrew shared their wish for the success of their enterprise. He could not resist looking at them once more. Believing their danger past, they sprang from their deadfall and, chirruping something in their shrill little voices and belongings up their skirts, their bare picayune sunburned feet scampered merrily and quickly across the meadow grass.

Prince Andrew was somewhat refreshed by having ridden off the dusty highroad along which the troops were moving. But not far from Baldheaded Hills he again came out on the route and overtook his regiment at its halting place by the dam of a small-scale swimming. It was past one o'clock. The sun, a red ball through the grit, burned and scorched his back intolerably through his black coat. The dust always hung motionless above the buzz of talk that came from the resting troops. There was no wind. Equally he crossed the dam Prince Andrew smelled the ooze and freshness of the pond. He longed to get into that water, however muddy it might be, and he glanced round at the pool from whence came sounds of shrieks and laughter. The small, muddied, green pond had risen visibly more than a foot, flooding the dam, because it was full of the naked white bodies of soldiers with brick-red hands, necks, and faces, who were splashing almost in it. All this naked white homo flesh, laughing and shrieking, floundered virtually in that dirty pool like carp stuffed into a watering can, and the suggestion of merriment in that floundering mass rendered information technology particularly pathetic.

One off-white-haired young soldier of the 3rd company, whom Prince Andrew knew and who had a strap circular the dogie of ane leg, crossed himself, stepped back to get a good run, and plunged into the water; another, a dark noncommissioned officeholder who was e'er shaggy, stood up to his waist in the water joyfully wriggling his muscular effigy and snorted with satisfaction as he poured the water over his head with hands blackened to the wrists. There were sounds of men slapping one another, yelling, and puffing.

Everywhere on the bank, on the dam, and in the swimming, there was good for you, white, muscular flesh. The officeholder, Timókhin, with his crimson little nose, standing on the dam wiping himself with a towel, felt confused at seeing the prince, but fabricated up his listen to address him notwithstanding.

"It'south very overnice, your excellency! Wouldn't you like to?" said he.

"It'southward dirty," replied Prince Andrew, making a grimace.

"Nosotros'll clear it out for you in a infinitesimal," said Timókhin, and, however undressed, ran off to articulate the men out of the pond.

"The prince wants to breast-stroke."

"What prince? Ours?" said many voices, and the men were in such haste to clear out that the prince could hardly stop them. He decided that he would rather wash himself with water in the barn.

"Mankind, bodies, cannon fodder!" he thought, and he looked at his own naked body and shuddered, not from cold but from a sense of disgust and horror he did not himself understand, angry by the sight of that immense number of bodies splashing about in the dirty pond.

On the seventh of August Prince Bagratión wrote as follows from his quarters at Mikháylovna on the Smolénsk road:

Dear Count Aléxis Andréevich—(He was writing to Arakchéev but knew that his letter would be read by the Emperor, and therefore weighed every word in information technology to the best of his ability.)

I expect the Minister (Barclay de Tolly) has already reported the abandonment of Smolénsk to the enemy. It is pitiable and sorry, and the whole army is in despair that this most important place has been wantonly abandoned. I, for my part, begged him personally about urgently and finally wrote him, simply nothing would induce him to consent. I swear to y'all on my laurels that Napoleon was in such a fix every bit never before and might accept lost one-half his ground forces just could not have taken Smolénsk. Our troops fought, and are fighting, as never before. With fifteen thousand men I held the enemy at bay for xxx-five hours and beat him; just he would non hold out even for fourteen hours. It is disgraceful, a stain on our army, and as for him, he ought, it seems to me, not to alive. If he reports that our losses were great, it is non true; maybe almost four thousand, not more than, and not even that; but even were they ten yard, that's state of war! But the enemy has lost masses....

What would it have cost him to hold out for another two days? They would accept had to retire of their ain accord, for they had no h2o for men or horses. He gave me his word he would not retreat, but suddenly sent instructions that he was retiring that night. We cannot fight in this mode, or we may presently bring the enemy to Moscow....

There is a rumor that you are thinking of peace. God foreclose that y'all should make peace afterwards all our sacrifices and such insane retreats! You would set up all Russia against yous and everyone of us would feel ashamed to wear the compatible. If it has come up to this—nosotros must fight as long as Russia can and as long every bit there are men able to stand....

Ane man ought to exist in command, and not two. Your Minister may peradventure be good equally a Minister, but as a general he is not only bad but execrable, still to him is entrusted the fate of our whole country.... I am actually frantic with vexation; forgive my writing boldly. It is articulate that the man who advocates the conclusion of a peace, and that the Minister should control the army, does non dear our sovereign and desires the ruin of us all. So I write yous bluntly: call out the militia. For the Government minister is leading these visitors after him to Moscow in a most masterly manner. The whole regular army feels great suspicion of the Imperial aide-de-camp Wolzogen. He is said to be more Napoleon's homo than ours, and he is e'er advising the Minister. I am not merely civil to him just obey him like a corporal, though I am his senior. This is painful, but, loving my benefactor and sovereign, I submit. Only I am pitiful for the Emperor that he entrusts our fine army to such as he. Consider that on our retreat we have lost past fatigue and left in the hospital more fifteen chiliad men, and had we attacked this would not have happened. Tell me, for God's sake, what will Russia, our mother Russian federation, say to our being so frightened, and why are we abandoning our skilful and gallant Fatherland to such rabble and implanting feelings of hatred and shame in all our subjects? What are we scared at and of whom are nosotros afraid? I am not to blame that the Government minister is vacillating, a coward, dense, dilatory, and has all bad qualities. The whole army bewails it and calls downwards curses upon him....

Source: https://www.marxists.org/archive/tolstoy/1869/war-and-peace/book-10-chapter-5.html

Post a Comment for "Chapter 5 War Peace and War Again"